Vector tiles have been around for a while and they seem to combine the best of both worlds. They provide design flexibility, something we usually associate to vector data, while enabling fast delivery, like we generally see on raster services. The mvt specification, based on Google’s protobuf format, packages geographic data into pre-defined roughly-square shaped “tiles” for transfer over the web.

The OGC API – Tiles standard, enables sharing vector tiles while ensuring interoperability among services. It is a very simple format, which formalizes what most applications are already doing in terms of tiling, while adding some interesting (optional) features. You can find more information on: tiles.developer.ogc.org .

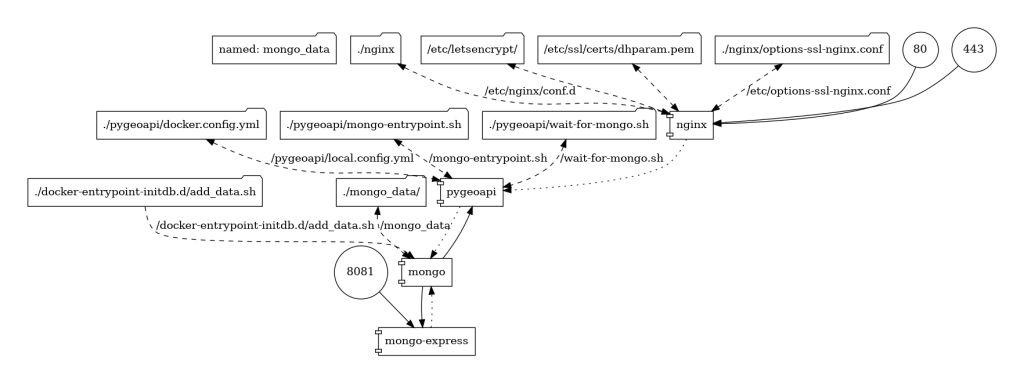

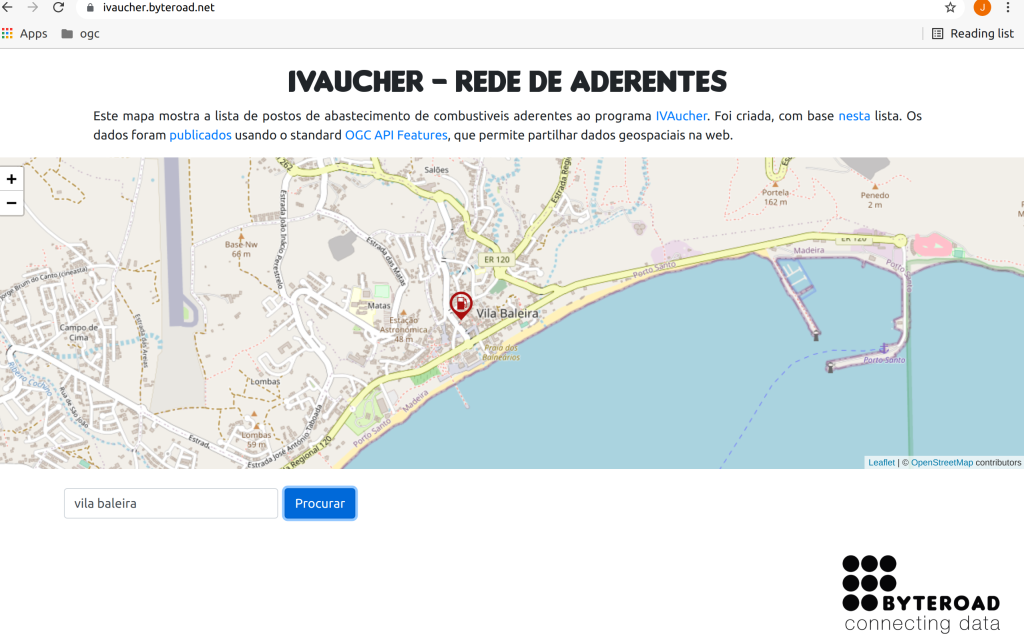

If you want to publish vector tiles using this standard, you could use pygeoapi, which is a Python server implementation of the OGC API suite of standards and a reference implementation of OGC API – Tiles. With its plugin architecture, pygeoapi supports many different providers to render the tiles in the backend. One option could be to use the elastic search backend (mvt-elastic), which enables rendering vector tiles on the fly, from any index stored in elasticsearch. Recently, this provider also supports retrieving the properties (e.g.: fields) along with the geometry, which is needed for client side styling.

You can check some OGC API – Tiles collections in the eMOTIONAL Cities catalogue. On this map, we show the results of urban health outcomes (Prevalence rates of cardiovascular diseases) in 350m hexagonal grids of Inner London. It is rendered according to the mean value.

On the developer console, we can inspect how the attribute values of the vector tiles are exposed to the client.

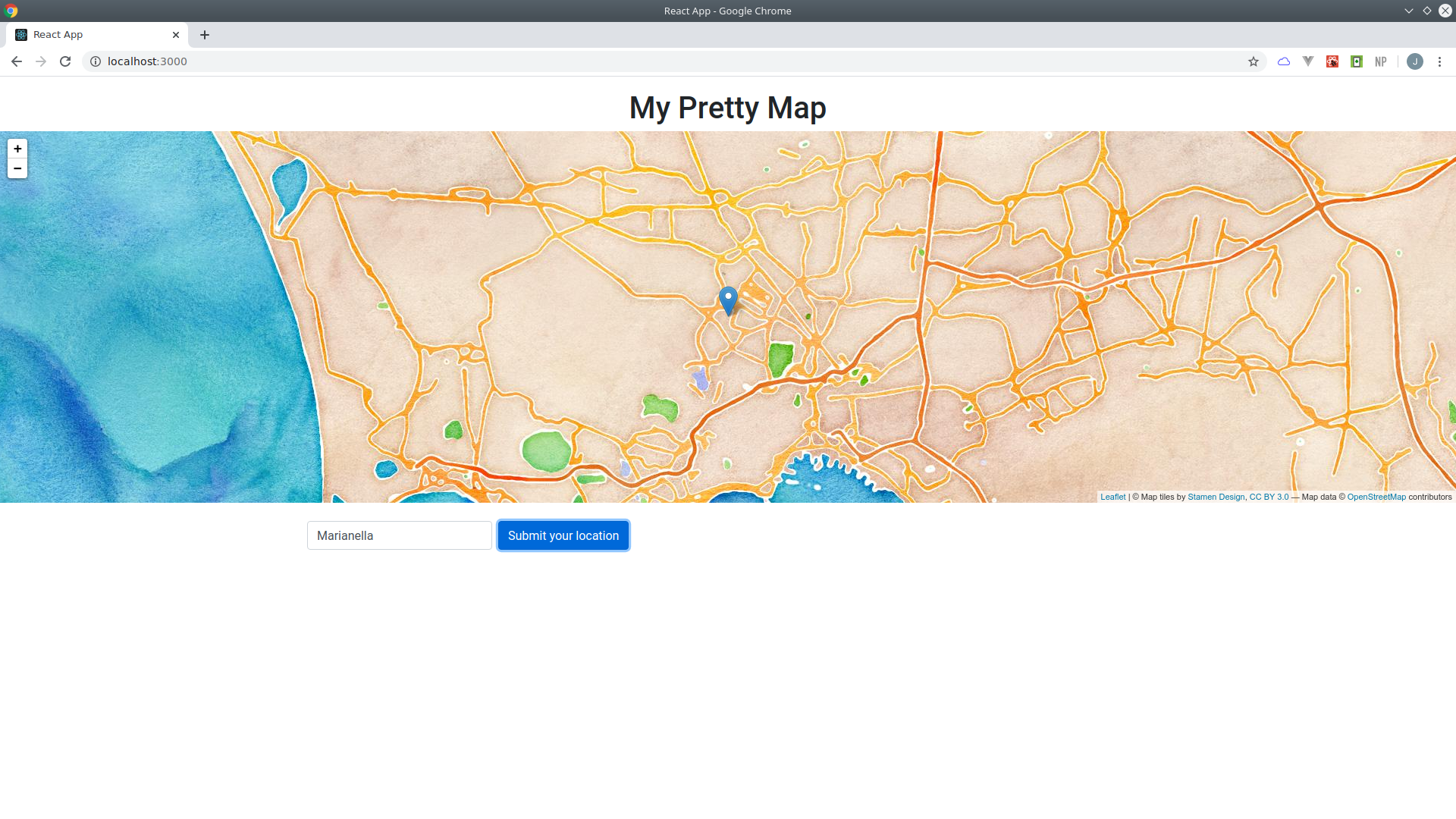

Another option for interactive maps that require access to attributes, would be to retrieve a GeoJSON from an OGC API – Features endpoint. In that case, the client would need to load all the features at the start, and then carry these features in memory. If we have a high number of features, or many different layers, this could result in a less responsive application.

As an experiment, we loaded a web application with a base layer and two collections with 3480 and 3517 features (“hex350_grid_cardio_1920” and “hex350_grid_pm10_2019”). When the collections were loaded as vector tiles, the application took 20 milliseconds to load. On the other hand, when the collections were loaded as features it took 6887 milliseconds.

You can check out the code for this experiment at: https://github.com/emotional-cities/vtiles-example/tree/ecities and a map showing the vector tile layers at: https://emotional-cities.github.io/vtiles-example/demo-oat.htm